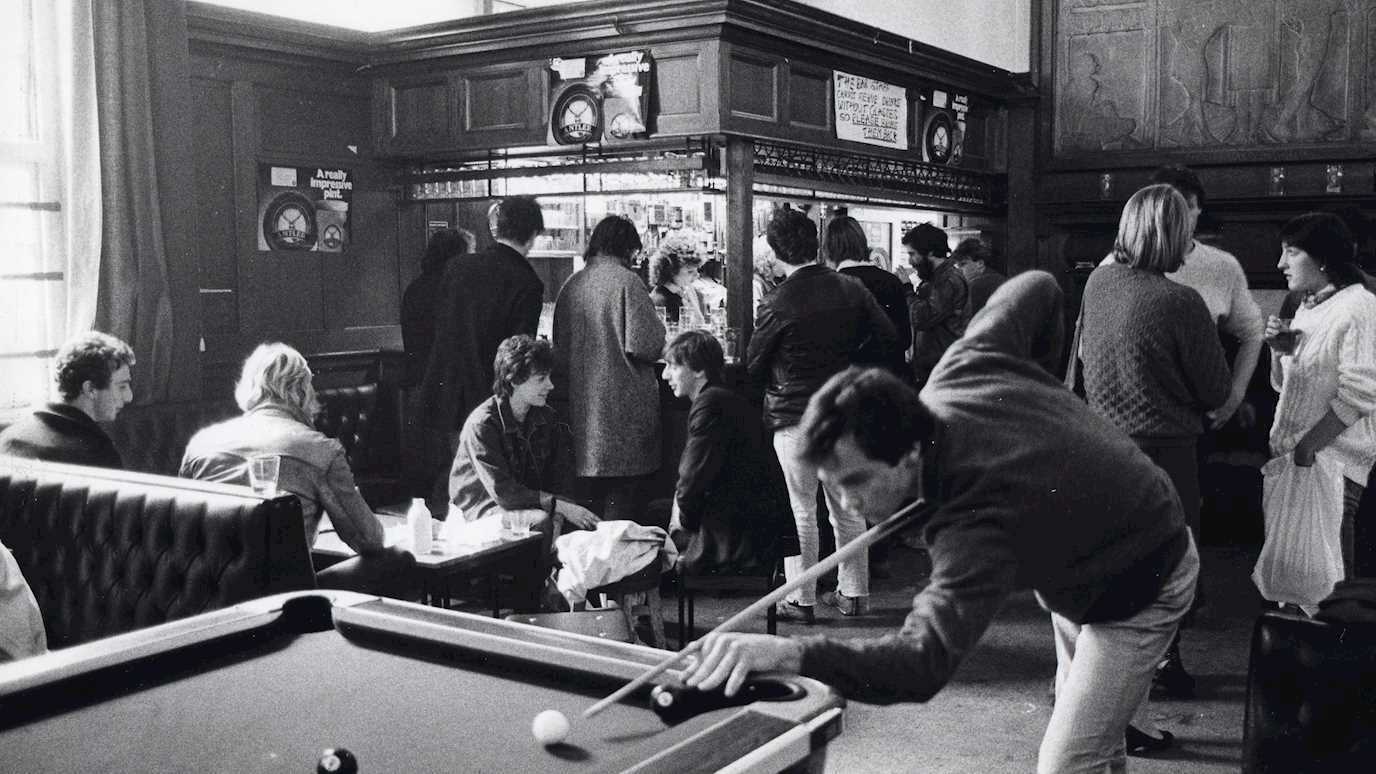

Professor Caroline Barron reflects on her time at Bedford College.

An image of students at Bedford College

Looking back on the years 1965 to 1985 when I was a member of the History Department at Bedford College in Regent’s Park I call to mind two aspects of my time there: the Place and the People.

The Place was, indeed, exceptional and remarkably beautiful. When I joined the History Department as one of two lowly Tutorial Research Fellows with a mere two years of historical research under my belt, I was allocated a room for tutorials on the top floor of Herringham. From my window I looked out across Regent’s Park towards the Boating Lake. At lunch I would join a high table in Herringham Hall where the staff from all Departments would meet for a ‘proper’ lunch followed by leisurely coffee and gossip in the Common Room on the ground floor of Tuke. In 1967 the History Department moved out of the main Bedford buildings to the Regency villa known as St John’s Lodge, recently vacated by the Institute of Archaeology.

At first the History Department shared the building with the Principal who had a flat on the first floor, but before long the Principal was ousted by the Greek and Latin departments although we historians always considered ourselves to be the primary tenants of the building. My room was on the top floor and looked east across the forecourt to the wonderful secret garden which, while beautifully maintained by the gardeners of the Royal Park, was used almost exclusively by us. We had a history library in one of the grand downstairs rooms and lectured in the ball room in an aura of faded glamour: gilt mirrors and chandeliers. We also had many parties in these rooms. On the first floor was our common room which we shared with the classicists; the three large windows faced west into the wooded park.

When I first taught at Bedford we lived in Kentish town and I would walk from the bus stop in Albany Street up the cherry walk, seemingly always in a haze of pink cloud, and into the inner circle. Later when we moved to St John’s Wood my route then took me from the bus stop in Baker Street across the bridge over the boating lake and, skirting the College, past the band stand and so into the inner circle. On 20 July 1982, having followed my usual route into St John’s Lodge, perhaps half an hour after arriving, I heard an extraordinary bang. I thought a heavy object had fallen over in an adjoining room. But then the helicopters started to fly overhead and we learned that the bandstand and musicians of the Royal Green Jackets who were playing there for an audience lounging nearby in their deck chairs, had all been blown up by a terrorist bomb. For a time, the idyll of the Park was shattered. But the good memories of flickering sunshine, great trees heaving under the weight of their dark summer leaves, and the distant sound of children and transistor radios playing together gradually returned and the idyll revived.

Just as the Park was a constant presence, so were my colleagues. In those days academics moved around less and there were no sabbatical terms or demanding collaborative research projects in distant parts. So we stayed put. When I joined there were eight members of the Department headed by Bob Greaves. Then in order of seniority, came Robin Du Boulay, Hugh Lawrence, Nicola Sutherland, Ivor Burton, Theresa Hankey, Conrad Russell and Pamela Pilbeam. Ivor Burton soon defected to Social Policy and was replaced by Joe Crook. And when Bob Greaves retired he was replaced as Head of Department by Michael Thompson from UCL. The two tutorial fellows were replaced by Pene Corfield and when Theresa Hankey left for the University of Sussex, I moved into her job after only the ghost of an interview. And so the nine of us occupied the spacious rooms in St John’s Lodge, ate sandwiches together in the common room and taught most of the University of London History syllabus to the ninety students whom we had hand-picked at interview. There is no doubt that we lost contact with the other departments of the College (and this was a disadvantage when the College had to face the multiple merger projects in the 1980s) but we knew each other well and we knew our students – and they knew us. We had time to play tennis on the court in the garden of the Holme surrounded by sweet-smelling lime trees and to stumble through an annual cricket match with the students. There were Christmas parties and, even, on one occasion we found time to put on a series of playlets to entertain the students (and ourselves). In one memorable scene Hugh Lawrence and Joe Crook interviewed Pene Corfield, an aspiring bunny girl, for a place to read history at Bedford. The misunderstandings and double entendres may be imagined.

But the good times had to come to an end: in the 1960s, only one in ten of school leavers went on to higher education, but by the 1980s there had been a massive expansion: nearly 40% of the age group now went on to higher education, and the costs had to be reduced. A merger was inevitable and so we moved to Egham: by that time John Turner had replaced Michael Thompson who had moved on to be Director of the Institute of Historical Research and Conrad had left for Yale University and had been replaced by Peter Lake. But none of us left because of the merger and we all together joined the historians of Royal Holloway. Of course we were not happy to leave the privileged environment in which we had been able to teach and study and play, but we held together, wisely led by Hugh Lawrence and were graciously welcomed by our new colleagues at Royal Holloway. The merger of our two departments was easier for us than for some others because all the history departments of the University of London taught to a common syllabus, had a single examining board, and offered a dazzling array of optional and special subjects from which our students could choose courses in any of the history departments of the University.

So we became refugees: we came to a new and welcoming country and our lives moved onwards and, indeed upwards, but the memory of our old home and of the old ways of doing things, still lingered, and lingers still as an experience more easily felt than described.