Katie Docwra is in her second year of PhD research in Modern Languages, Literatures and Cultures. She holds a studentship funded by the AHRC Techne Doctoral Training Partnership. Here she reflects on a recent research trip to Paris.

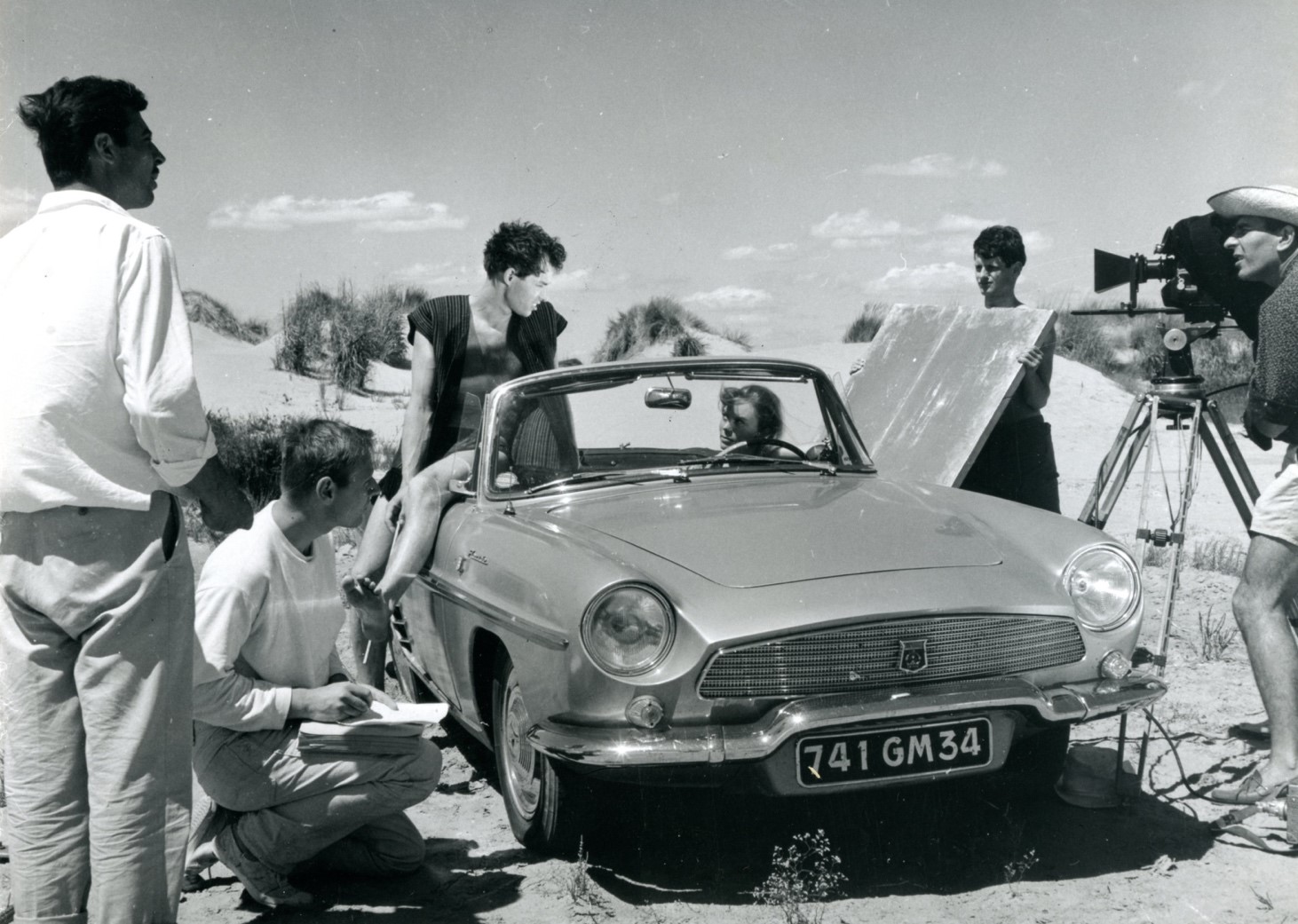

Paula Delsol filming La Dérive (1964). © Bernard Bastide

Having just completed my first year of postgraduate doctoral research, what better way is there to celebrate the occasion than to write about it? As the pressures of researching, writing, teaching commitments and balancing a personal life mount up, it is important to take a step back occasionally to reflect on progresses made and think about how to move forward. When people ask me if I enjoy my research, my resounding ‘yes!’ often yields a look of surprise alongside a knowing smile which implies that I will think differently in the near future. But having just completed a second research visit to Paris, the enthusiasm this trip has given me will no doubt see me through to the end.

Challenges

My research is focused on the work of French female director Paula Delsol, whose forty-year career spent writing and directing short and feature films, documentaries, novels and children’s stories, as well as several contributions to French television, has been widely unacknowledged both academically and commercially. In the little work that has been published in more recent years, Delsol has often been mislabelled as ‘lost’. But her contributions to French cinema and the moving image have been there all along, just waiting to be pulled out from the archives.

To my pleasant surprise, once I started looking I found that there was a wealth of information available. But that is not to say that researching Delsol has not been problematic, particularly as there has been no official deposit of her personal archives since her death in 2015. Any documents or footage that are available for consultation are distributed across the various French public institutions such as the Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée (CNC), the television and radio archives Inathèque and the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BNF), as well as the Cinémathèque Française, which is a private institution based in Paris and home to a vast collection of film archives. These various public institutions, whilst funded by the same government department, do not share resources and therefore the most basic research has been quite challenging. For example, Delsol is sometimes catalogued under Paula, the name she used from the 1970s onwards, but other works are referenced under Paule, her published name from the late 1950s. Other works are credited to her then husband, the cinematographer Jean Malige, which is not only erroneous but it occasionally prevents her work from being found in basic searches. So separate are the catalogue entries that sometimes it has felt as though I have been researching two different people.

A chance meeting

In June 2018, I took my first research trip to Paris, seeking out national and regional newspaper clippings, televised interviews, and viewing some of Delsol’s little-known television work including the final autobiographical documentary co-directed with her son, Bernard Malige, in the late 1990s. At the Cinémathèque Française, I joyfully sifted through a trove of archival collections belonging to other prominent names from French film history, including Louis Malle, Marcel Carné and Pierre Billard, all of which contain tiny snippets of information relating to Delsol. But most importantly, the Fonds Truffaut – the collection belonging to the Cahiers du cinéma critic and director operating in the iconoclastic Nouvelle Vague period – contains a significant amount of primary materials from Delsol herself, including a set of barely-touched letters between Delsol and Truffaut written throughout the 1960s, an early version of a script to her 1964 debut feature La Dérive (released in Anglophone markets as ‘Drifting’), as well as various legal documents.

The trip was successful not only due to the quantity of primary materials I could access, but because I happened to make the acquaintance of a prolific French film historian, Bernard Bastide, who has spent almost twenty years researching the early work of Delsol and Malige. We met entirely by chance when he sat down opposite me in the Cinémathèque Française researchers’ area which is available by appointment only. I recognised him immediately from a recent newspaper article he had published, and he recognised the documents I was studying almost as immediately. This first meeting led me to return to Paris for a second research trip six months later, to consult Bernard Bastide’s own archives that he agreed to share with me and to conduct an interview with Michka Gorki, a female director who began shooting a documentary about Delsol in the late 1970s which, sadly, remains unfinished. Most importantly, this recent trip involved two days at the CNC Archives françaises du film near Versailles, where I was able to consult some of Delsol’s early short films and documentaries. I was also able to finally view her second feature film, Ben et Bénédict (1977), which is not available commercially due to complicated distribution rights. I fell in love with the film immediately. After three consecutive viewings, it not only confirmed my interest in Delsol’s unique style but also allowed me to establish how I want to take my research forward.

Discovering Paula

What struck me the most during this second trip was how Delsol – this director I had only read about – suddenly came to life through the personal anecdotes that her professional and personal acquaintances shared with me. Listening to memories, looking at candid photographs taken during dinner parties, sharing in tales about her mannerisms, eccentricities, her favourite expressions, her love of animals, her sense of humour, as well as stories of a more private nature, suddenly changed everything. She became Paula, no longer just ‘Delsol’, and I started engaging with her work on a much deeper level than I did previously. I have learned, however, that the more information I gather, the more contradictions I find – not only in the myriad errors printed in different sources (birth place, film and book titles, etc.), but also in the conflicting accounts given by the director herself in different interviews throughout her career. Part of the challenge will be to explore these evolving self-narratives in a way that remains objective, without romanticising or rewriting the past.

Going forward, I am excited to bring back my findings and contribute to sharing knowledge about one of the most overlooked women in French cinema. Paula Delsol was never lost. We just weren’t looking hard enough.