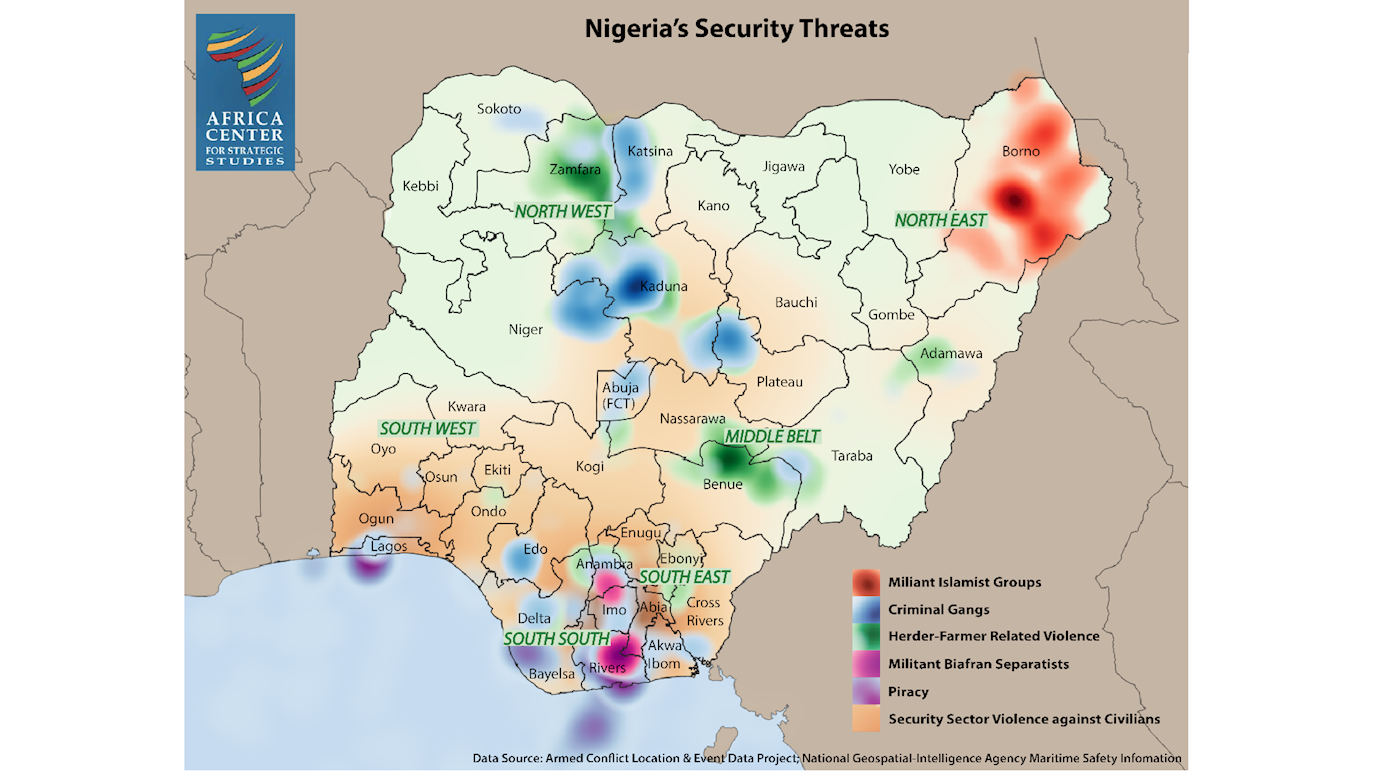

In Nigeria’s Middle Belt, competition for land and other resources has intensified between nomadic Fulani herders and sedentary farmers. What were initially sporadic conflicts over cropland and water resources have transformed into daily occurrences of mass violence. While extant research centers on the root causes of such conflicts, the reasons for their escalation remain insufficiently understood. This article by Ezenwa Olumba examines how political developments have contributed to the escalation of conflicts. Using the Homer-Dixon model and secondary sources, the findings show that changes in Nigeria’s “political opportunity structure” since 2014 were catalysts for escalating violent conflicts. The consequences were the unvarnished adoption of nepotistic domestic policies and alliances between elites and militia members, which escalated the violent conflicts. This article advocates the devolution of natural resources and security governance to prevent leaders from leveraging shifts in political opportunity structures to favour a specific demographic group.

On April 27, 2021, when gunmen attacked and killed seven people at an IDP camp in Benue State, Mr Samuel Ortom, Governor of Benue State, reacted by accusing Nigeria’s president of being a sectional president of the Fulani people. The President responded that the killings and violence in Benue State resulted from Mr. Ortom’s refusal to adopt “RUGA policy” and urged him to adopt it for the sake of peace. A few days later, as if exonerated by the President’s comments, Fulani gunmen attacked a Tiv community in Benue State, killing eleven people and displacing hundreds more. These mass killings and destructions are distinct from Boko Haram terrorist attacks. Boko Haram and its affiliates are Islamist terrorist organisations that seek to destabilise Nigeria’s secular government and replace it with one based on a strict interpretation of Sharia law. Most Boko Haram militants are said to be Muslims from the Kanuri ethnic group in Nigeria. In contrast, the killings reported above are tied to eco-violence, a conflict over water and agricultural resources in Nigeria’s Middle Belt between nomadic Fulani herders and sedentary farmers. There are, however, signs of a link between Boko Haram terrorist cells and militant herding communities.

The synergy of forces between leaders and militants can escalate mass violence and killings when the majority of the population remains fearful and the radical group has won an election.128 In the Nigerian context, some elites have been accused of collaborating with militants on both sides of the conflict. For instance, the former Minister of Defence, General Theophilus Danjuma, urged Nigerians to “defend yourselves or you will all die” because the security forces in Nigeria are colluding with Fulani herders to attack communities.129 A report corroborated the claim that the military collaborated with Fulani herders to kill people.130 Sheikh Ahmad Gumi accused some segments of the Nigerian military of “arming” and “colluding” with the Fulani militia and described the ongoing eco-violence in Nigeria as a “tribal war” between the Fulani herders and other “tribes.”131 Both assertions of military-herder coordination appear plausible, given that both were senior military officers and prominent Nigerians with reputations to preserve. Some clergy and leaders of cattle breeders’ associations facilitate ransom negotiations on behalf of the Fulani herders.132

The governor of Kaduna State, Mallam Nasir El-Rufai, has been accused of taking sides in the eco-violence in Southern Kaduna.133 However, Mallam El-Rufai claimed that he used government funds to bribe some Fulani herders to desist from killing farmers in Southern Kaduna.134 This situation is comparable to a scenario in which the governor of New York bribes terrorists not to murder civilians in New York neighbourhoods. In Benue State, some politicians were accused of collaborating with Mr. Terwase “Gana” Akwaza.135 The former and incumbent Governors of Benue State, Mr. Gabriel Suswan and Mr. Samuel Ortom accused the Nigerian Army of extra-judicial killing of “Gana.”136 Mr. “Gana” was a “feared leader” of a Tiv militia group credited with defending the Tiv people against Fulani herds and Jukun people; he was also labelled as a “dreaded criminal.”137

Mr. Femi Adesina’s opinions on eco-violence on AIT TV might be seen as tacit support for the Fulani herds. He said:

"Ancestral attachment? You can only have ancestral attachment when you are alive. If you are talking about ancestral attachment, if you are dead, how does the attachment matter? If your state [government] genuinely does not have land for ranching, it is understandable. But where you have land and you can do something, please do for peace. What will the land be used for if those who own it are dead at the end of the day?"138

In other words, for peace to prevail, the administration of President Buhari invites citizens to surrender their land to Fulani herders; if they do not, they risk losing their lives and land. Such a stance can increase grievances on both sides because people’s behaviour in a political system is determined by the kind of “opening,” obstacles, and resources provided by the political system.139

Impunity is another issue that has resulted from the shift in the political opportunity structure; most of the perpetrators of eco-violence are never apprehended or prosecuted. For example, Mr. Garius Gololo, the head of a Fulani socio-cultural group who claimed responsibility for the New Year’s Eve massacre, has yet to face charges.140 Similarly, no member of the Fulani Nationality Movement (FUNAM), which claimed responsibility for the attempted assassination of the governor of Benue state in March 2021, has been apprehended.141

You can read the full article here.

Ezenwa Olumba is a PhD candidate in the Department of Politics and International Relations, Royal Holloway, University of London. His teaching and research interests lie at the intersection of politics and migration. His geographical expertise is within Africa and mainly the West African sub-region. Eze is currently engaged in an interdisciplinary project that focuses on issues at the nexus of armed conflict and (im)mobility, emphasising realities in the Sahel of Africa and, particularly, households' aspirations for immobility during times of violence.