Dr Barbara Zipser is the Principal Investigator on an interdisciplinary research project, Plants and Minerals in Byzantine Popular Medicine: A Multidisciplinary Approach (Welcome Trust Collaborative Award), working with an international group of ethnopharmacologists, botanists, and a geologist to develop a new methodology of identifying medicinal plants described in ancient and medieval sources.

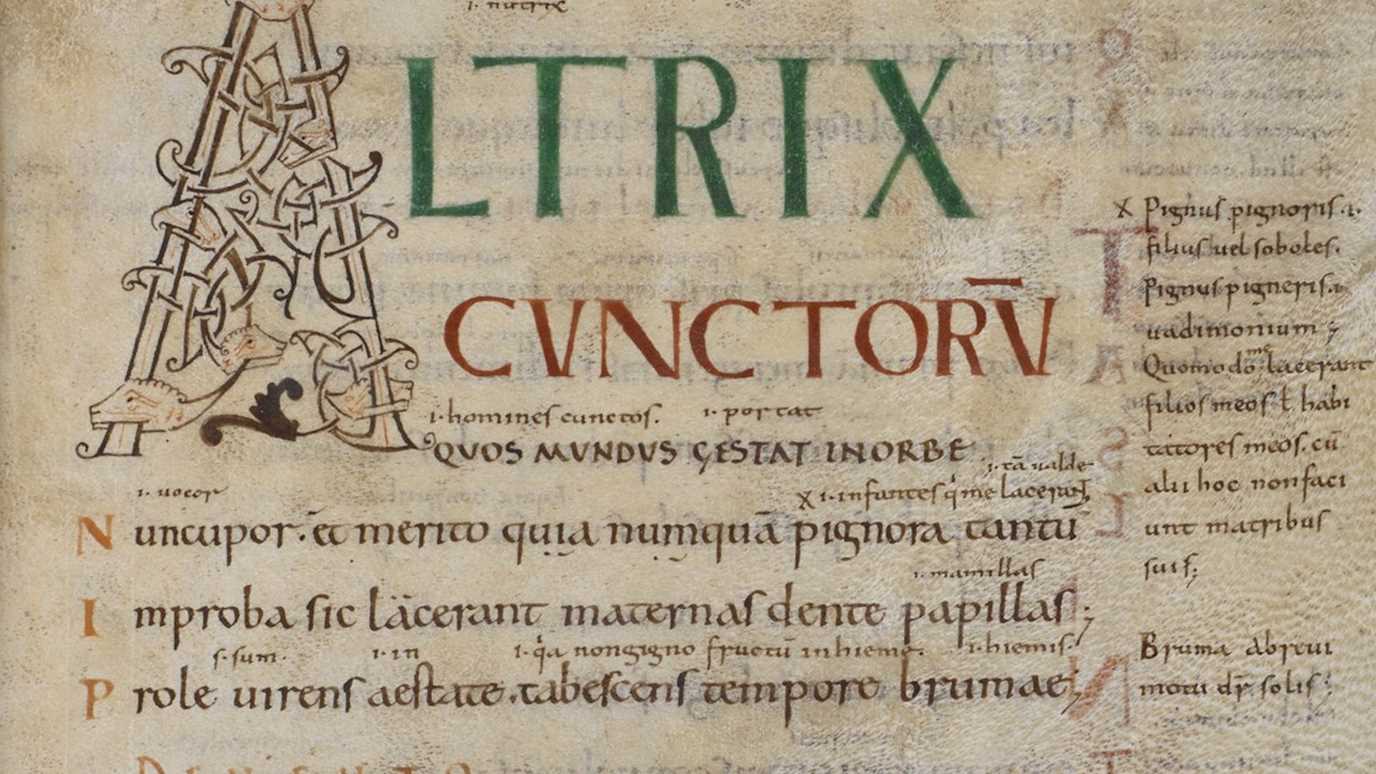

Illustrations of plants from a medieval manuscript

Many of our most commonly used modern medicines are derived from plants. Some medicines like aspirin (derived from willow bark) have been in continuous use for millennia. Other plants used successfully to treat disease in Antiquity and the Middle Ages later fell out of fashion, leaving the secret of their valuable properties locked in manuscripts, waiting to be rediscovered by Dr Zipser and her scientific collaborators.

Understanding ancient and medieval usage of medicinal plants can help modern scientists derive new drugs for treating modern diseases. This process begins with screening plants based on historical information; if a plant was used to alleviate certain ailments in the past, it might be valuable in treating similar diseases now. Ancient plant knowledge can also help in testing already-known drugs to see if they have effects on other diseases, by identifying potential additional uses for plant-derived drugs. Such a trial is currently underway on a traditional gout drug – derived from an ancient plant – to see if it has a beneficial effect on Covid-19 patients.

Success in developing ancient and medieval remedies into modern medicines requires precise identification of the plants described in historic sources. Common, and even scientific plant names might have changed or been re-used for different plants throughout the centuries. Plants called the same thing in different areas (for example, ‘bluebells’) might not be at all the same botanically, or the exact same plant might be given various names in different regions of a country. Dr Zipser notes that as the project team worked, ‘it became clearer that a methodology was needed’ to clearly identify plants, classify and categorise them. Understanding precisely what ancient and medieval authors meant requires Dr Zipser’s expertise in philology and the history of medicine.

The project traces its origins to a problem of translation that Dr Zipser first noticed when she was 16. While translating a passage from Homer that describes Ogygia, the island home of the nymph Calypso, where ‘soft meadows of violets and parsley were blooming’, she asked her teacher how a translator could be sure that Homer had meant to describe the plant that we commonly call parsley. The German word for parsley (Petersilie) derives from the Greek petroselinon, as does the English, but parsley and violets do not bloom at the same time. Perhaps Homer was referring to a different plant altogether?

Years later, Dr Zipser met a Zürich-based ethnopharmacologist who had worked on Cypriot plant-based medicines named in medieval sources. A colleague from the Geology department at Royal Holloway introduced her to two collaborators from Kew Gardens. Later an Israeli collaborator with a background in medical history and pharmacy added his expertise on Hebrew and Arabic sources and modern-day uses of traditional medicines.

Dr Zipser notes that it is ‘powerful to join forces across disciplines’ to work on a project like this; humanists can take a great deal of knowledge from scientists, and vice versa. Collaborators with very different disciplinary backgrounds can nevertheless have much in common; for example, medieval lexicography (dictionary-making) is one of Dr Zipser’s specialties, and one of her scientist collaborators works to develop a database of standardized plant names that is used by scientists and governments worldwide. Their collaboration on this project has allowed each of their specialties to inform the other, ultimately producing research with both deep historical interest and crucial medical applications both in the present and for tomorrow.

Dr Barbara Zipser was interviewed by Charlotte Gauthier, a PhD student in History and Engaged Humanities Officer.