If I were to mention Royal Holloway’s 1632 edition of Shakespeare’s Second Folio, I can guarantee most people would be impressed. But how would they feel knowing it had been tampered with?

Our pristine edition lacks one iconic component: Martin Droeshout’s engraved portrait of William Shakespeare. This portrait, seen in Fig. 1, beautifully graces the cover of the 1623 First Folio and what we know as nearly all Second Folios. Yet, within our edition there has been a manual ‘copy and paste’. As seen in Fig. 2, our frontispiece now features a new title, new printer, new date, and, most importantly, a new Shakespeare.

Martin Droeshout (1601–1650) was a London-born engraver of Flemish descent. His well-known portrait of Shakespeare for the First Folio (1623) is probably the most familiar image of the playwright. Droeshout came from a family of engravers and was probably trained by his father. Despite its fame, his Shakespeare portrait has received criticism for its somewhat naive artistic style. However, its authenticity was vouched for by Shakespeare's contemporaries, including Ben Jonson, who described it as capturing the playwright's "true likeness."

The Second Folio, published in 1632, retained Droeshout's portrait. However, the copy from Royal Holloway broke apart from the lot. Instead of Droeshout's engraving, there is a substitute portrait, clearly altered after the book's initial printing.

Through my research, I've aligned this portrait with John Goldar's 1785 engraving (Fig. 3). John Goldar, an engraver based in Great Britain, was noted for the minute details he brought to his works, and he frequently reprinted Shakespearean images for audiences of the 18th century, including that of James Lackington: the man who revolutionised British book trading. Yet, it is important to note that this is not one of the more popular portraits of Shakespeare, raising a compelling question: Who altered this edition, and why?

The National Gallery states that this engraving most likely followed "John Taylor's line engraving" (1785). However, this portrait has come under scrutiny in multiple publications, one of note being Tanya Cooper's essay Searching for Shakespeare (accompanying the exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, which displays this portrait, from 2 March - 29 May 2006) but also in earlier publications, including some of the renderings discussed in George Virtue's The Dramatic Works of William Shakespeare (1849), which included A. Wivell's inquiries into Shakespearean portraiture authenticity.

Is one to assume that this edition was being remodelled for a newer audience? Or to "improve" Shakespeare's image for a collector or scholar? While we know our folio is authentic in the original print, these dates would suggest the tampering occurred from a person from the 18th or 19th century who had removed Droeshout's engraving and replaced it with a more modern or aesthetically pleasing one. However, the motives for this replacement remain mere speculation.

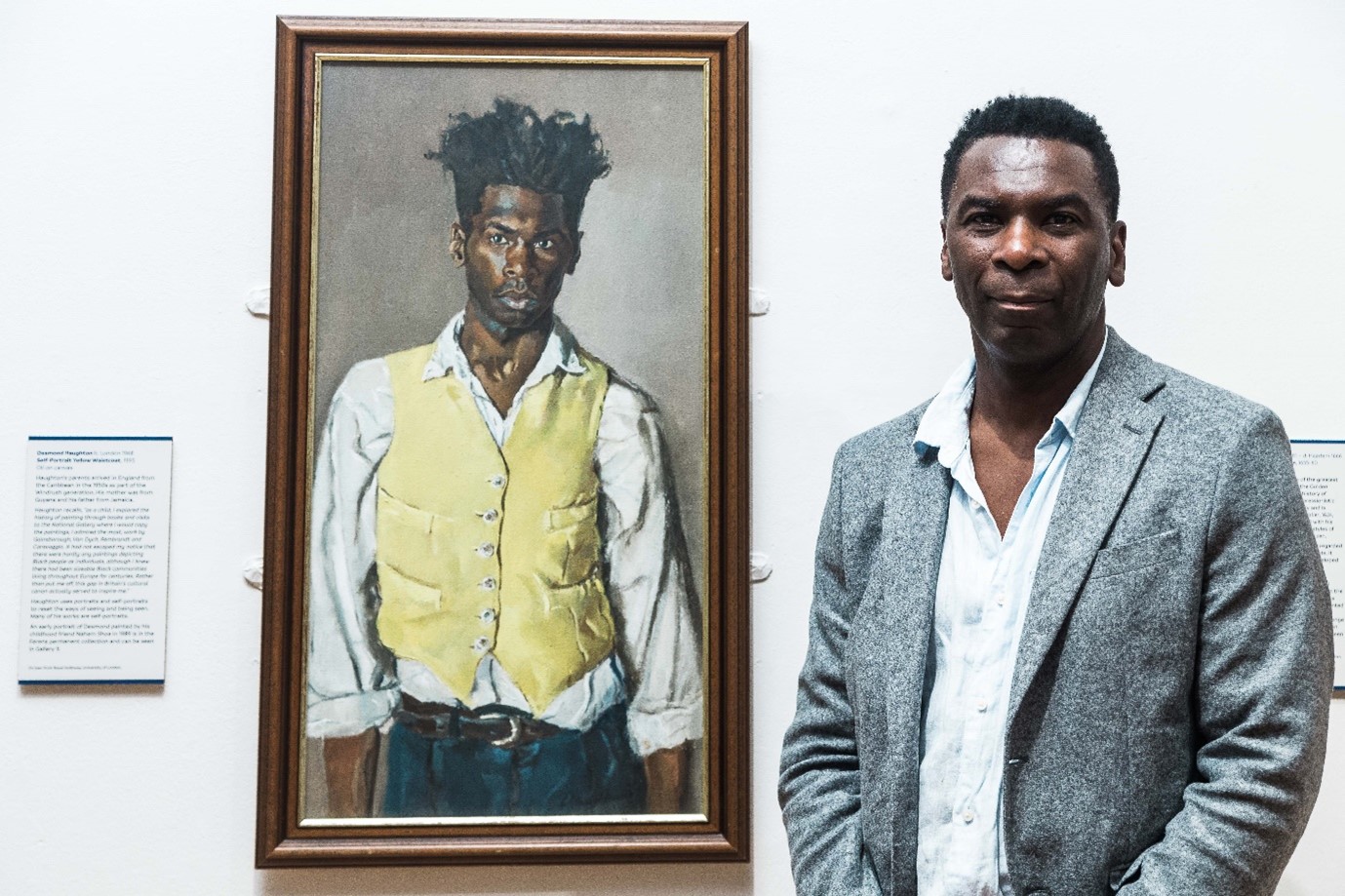

The Royal Holloway Second Folio entered the Bedford Collage Archive in 1903 (shown in Fig. 6.), gifted by the esteemed Frederick James Furnivall. If one doesn’t know already, Furnivall's input to English literary studies was enormous. He founded a series of scholarly and philological societies: the Early English Text Society (1864), the Chaucer Society (1868), the Ballad Society (1868), the New Shakespeare Society(1873), the Browning Society (1881, with Emily Hickey), the Wyclif Society (1882), and the Shelley Society (1885), while also contributing to the protracted genesis of the Oxford English Dictionary.

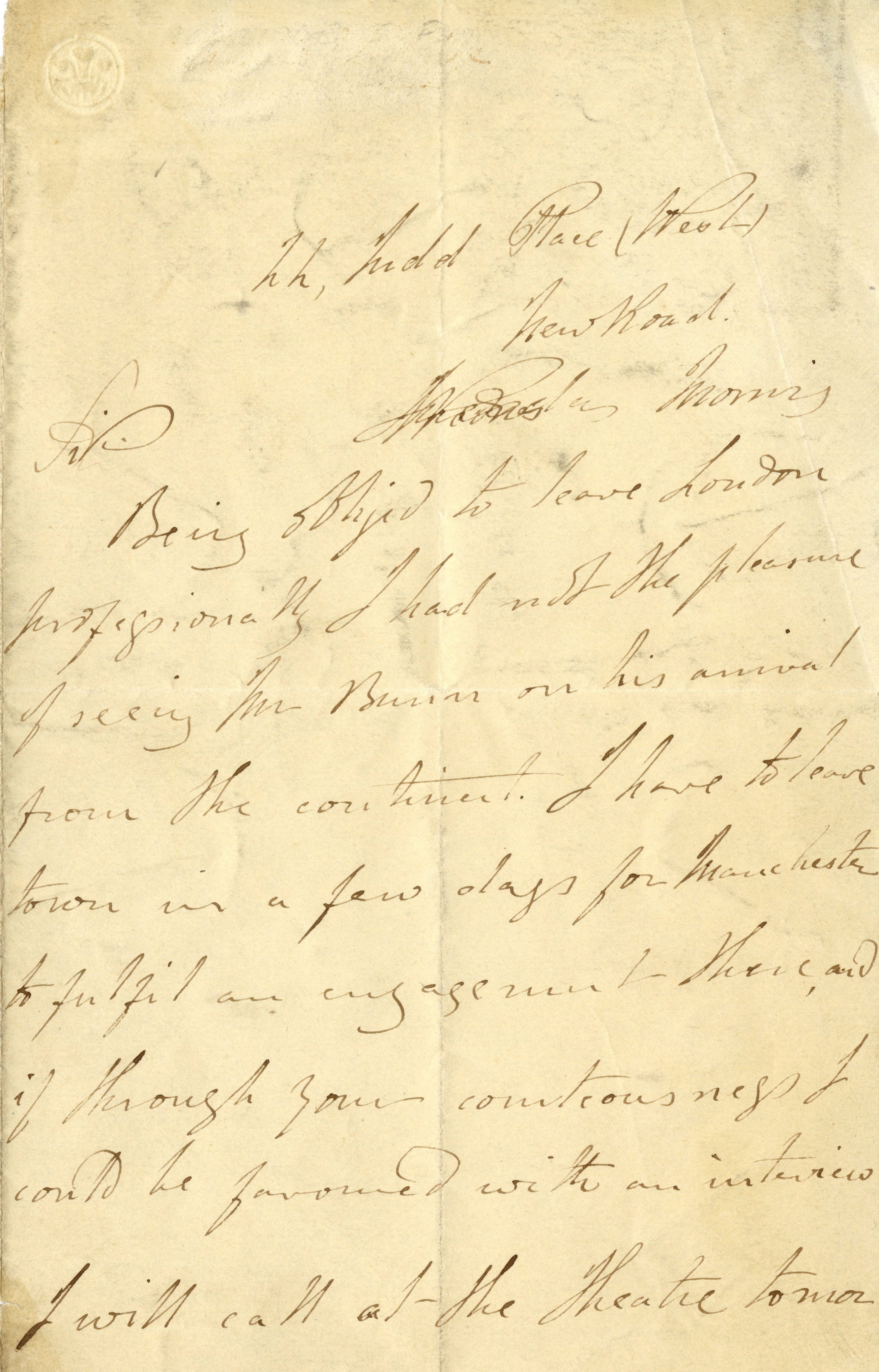

It seems like we can figure out when Furnivall received this text too. As shown in Fig 7, which I have transcribed as saying “New Shakespeare Society, 1879.” However, Furnivall’s role as a Shakespearean scholar and the founder of the New Shakespeare Society might explain the tampering of this edition.

It’s essential to recognise that Furnivall’s reputation was marred by controversy and sometimes editorial inconsistencies—more accurately characterised as tampering. But does this allow us to presume Furnivall is our secret editor?

While no evidence directly implicates and, in fairness, a significant gap exists between his ownership in 1879 and the book’s original printing. His intense focus on Shakespeare's works—and the Victorian penchant for "improving" historical artefacts—cannot be ignored. His involvement adds an additional layer of intrigue to the already puzzling history of this edition.

However, to further complicate this, the Royal Holloway Second Folio contains a handwritten note citing Lowndes' Bibliographer's Manual (Fig. 8. which I have transcribed): "Title- on which is the portrait of Shakespeare by Martin Droeschout." This runs contrary to the folio's present state, naturally leading us to question: did the annotator see the folio in its earlier state with the portrait, or was this a misinformed assumption, given their knowledge of Second Folios? If the annotations within are attributed to the Society, they imply that Droeshout’s original portrait was once present. This suggests the substitution occurred either before the Society’s acquisition or during its custody, potentially involving multiple individuals rather than Furnivall alone.

One further curiosity about this edition is the erroneous assignment of its printer. The title page ascribes it to "John I" in 1622 (Fig. 9.)—two mistakes in a single breath. First, the Second Folio was published in 1632 (although some of its remainder issues were released as late as 1641 and after), not 1622. Second, it was published by Thomas Cotes, not John I.

The Second Folio was by a syndicate of publishers whose imprints are displayed on the title page and elsewhere: Robert Allot, William Aspley, John Smethwick, Richard Hawkins, and Richard Meighen. Of the five, Allot's issues are the most common, while the Hawkins issue is scarce.

The attribution, or perhaps misattribution to "John I", I presume, was either a personal dedication to someone (of which, to my knowledge, no history is known), a deliberate forgery, or an interpolation error. Or are we to take a leap and assume this is the beginning of a dedication to the portrait artist? Or perhaps the "I" is a typo for "John T", for John Taylor? Or a member of The New Shakespeare Society that we have yet to allocate?

The tampered frontispiece, misprinted details, and annotations raise more questions than answers. Here, Royal Holloway has an edition truly one of a kind, making it invaluable in its own right.

This edition points to a history that is singular but significantly altered. This article only touches the tip of the iceberg, as there is so much more to be explored and said about this legendary copy and its annotations.

In the end, this folio gives a fascinating glimpse of how the idea of Shakespeare has been formed and re-formed century after century.

But what do you think it is- a priceless rarity or a flawed relic? Perhaps the answer does not lie in the artefact alone but in the story behind it. To find out more and see this unique peculiarity for yourself, come down to the Royal Holloway Archives and Special Collections!

Written by Ella-Rose Parkin, 3rd year English

- Cooper, Tanya. Searching for Shakespeare. Exhibition Catalogue. National Portrait Gallery, 2006.

- Droeshout, Martin. "William Shakespeare Portrait." First Folio. London: Printed by Isaac Jaggard and Edward Blount, 1623.

- Furnivall, Frederick James. Records of the New Shakspere Society. London: Trübner & Co., 1876.

- Goldar, John. "William Shakespeare, Engraving after John Taylor's Portrait." London, 1785.

- Lowndes, William Thomas. The Bibliographer's Manual of English Literature. London: Bell & Daldy, 1857.

- Virtue, George (Ed.). William Shakespeare: The Dramatic Works of William Shakespeare. With an Original Memoir... by A. Wivell, Esq. London: Virtue & Co., 1849.

- West, William. The Shakespeare First Folio: The History of the Book. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Further References:

- National Portrait Gallery. John Taylor's Portrait of William Shakespeare. Exhibition. Notes, 2006.

- "National Portrait Gallery – Portrait NPG 1; William Shakespeare". London: National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- Royal Holloway Archives. The 1632 Second Folio of Shakespeare. Manuscript Record, 1903.

- Sidney Lee. Shakespeare and the Portraits of the Author. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1904.

- Shakespeare, William. Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies. Published According to the True Originall Copies. 2nd ed., 1632. Folger Shakespeare Library, http://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet/s/868d4l.