Cabinet ministers rarely comment on museum policies. Still rarer do Classical artefacts become front-line news in the cultural wars. But the Parthenon Marbles are an exception. The recent visit of the Greek Prime Minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, became a full-scale diplomatic spat when Mitsotakis restated, in answer to a direct question, the long-held Greek policy that the Marbles be returned to Athens. Rishi Sunak cancelled meetings, issued press releases, and despatched his culture warriors to go out and brief the press. My informants at the Greek embassy tell me that Mitsotakis, who learnt of his cancellation from X, was initially annoyed, then delighted. He was in London for a relatively low-key celebration of the life of Lord Byron, the Romantic poet and fighter for Greek freedom. But now his visit was headline news in Britain and Greece. The Prime Minister could be seen as standing up for Greek culture and heritage. The Parthenon Marbles were being debated and discussed and this coverage was the only way he could advance his country’s case. Whether this played well for Mr Sunak is not so obvious.

Royal Holloway Classics had already booked Professor Angelos Chaniotis of Princeton University to deliver the Dabis lecture, our annual summer public lecture. Angelos has a claim to be the most eminent living historian of the ancient Greek world. He advises a host of cultural institutions on their cultural policies including the New York Metropolitan Museum. There is no-one who is in a better position to provide an insight into the debates on the Marbles. I was honoured to respond to his lecture.

Angelos took us through the cultural and legal arguments. The marbles have been in the UK for 212 years and were on the Parthenon in Athens for nearly 2,300 years before being removed by Lord Elgin. In the UK, the marbles are often called ‘The Elgin Marbles’, which is bit like associating the Mona Lisa with Francis I of France rather than Leonardo da Vinci. Angelos demolished the legal arguments that Elgin had legal rights over the marbles. Those argument were regarded as spurious by many in the late eighteenth century. Even since the lecture, those legal arguments have been further questioned by the absence from the extensive Ottoman archives of any record of Elgin’s permission to remove the marbles. And, as a note, the Ottoman bureaucracy was extensive and their archives are extraordinary in their completeness: such a legal document should be there. Angelos showed how the separation and removal of the marbles is contrary to UN cultural heritage agreements, which establish ground rules for museums and the restoration of looted artefacts. He argued for a reconnection of the marbles, which are architectural features, with the Parthenon on art historical grounds and in restitution of a historical wrong.

My contribution was to situate the debate within the legacies of colonialism, not just Ottoman domination of Greece, but also of the subsequent Western European attitudes towards Greece. After the Greek War of Independence in the first half of 19th century, the Great Powers installed a Bavarian government. They justified this by arguing that the Greeks were unfit to rule themselves. One consequence was to see the Greeks not as heirs to their Classical legacy, and to claim that Greek Classics belonged to Europe. Thus, Classical Greek artefacts were better located in the great museums of the colonial powers. That argument has been maintained, even if moderated, over the subsequent centuries, and explains why little annoys my Greek friends more quickly than the UK’s political statements about the marbles: they are part of a long history of the (former) Great Powers diminishing the Greek state and Greeks themselves.

The argument on the Marbles is caught up in nationalism and colonial legacies. That poses a problem. It is almost an article of faith in our Royal Holloway community that:

Classics belongs to no one Classics belongs to everyone

This is central to our teaching and research. We would not endorse a Greek nationalist claim to the Marbles nor a British colonial claim. So where should the Marbles be?

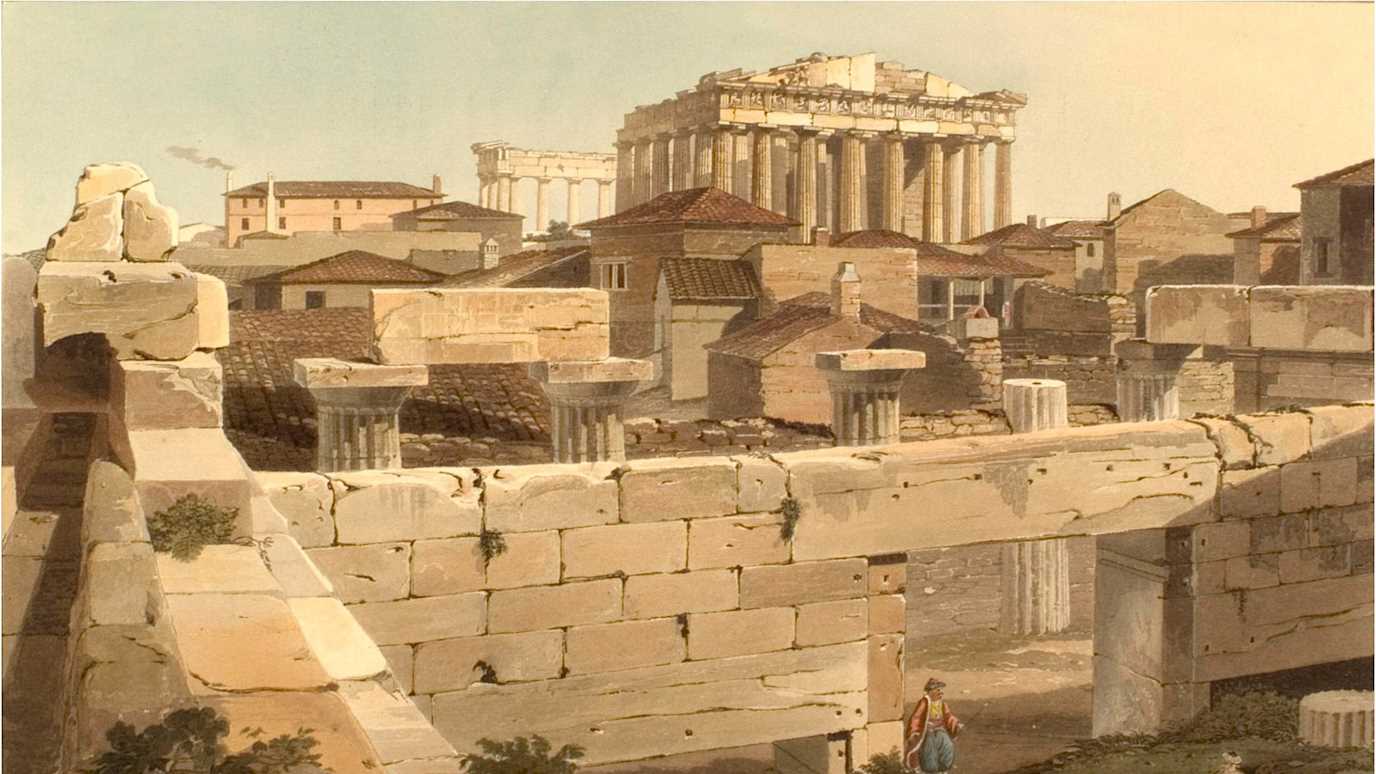

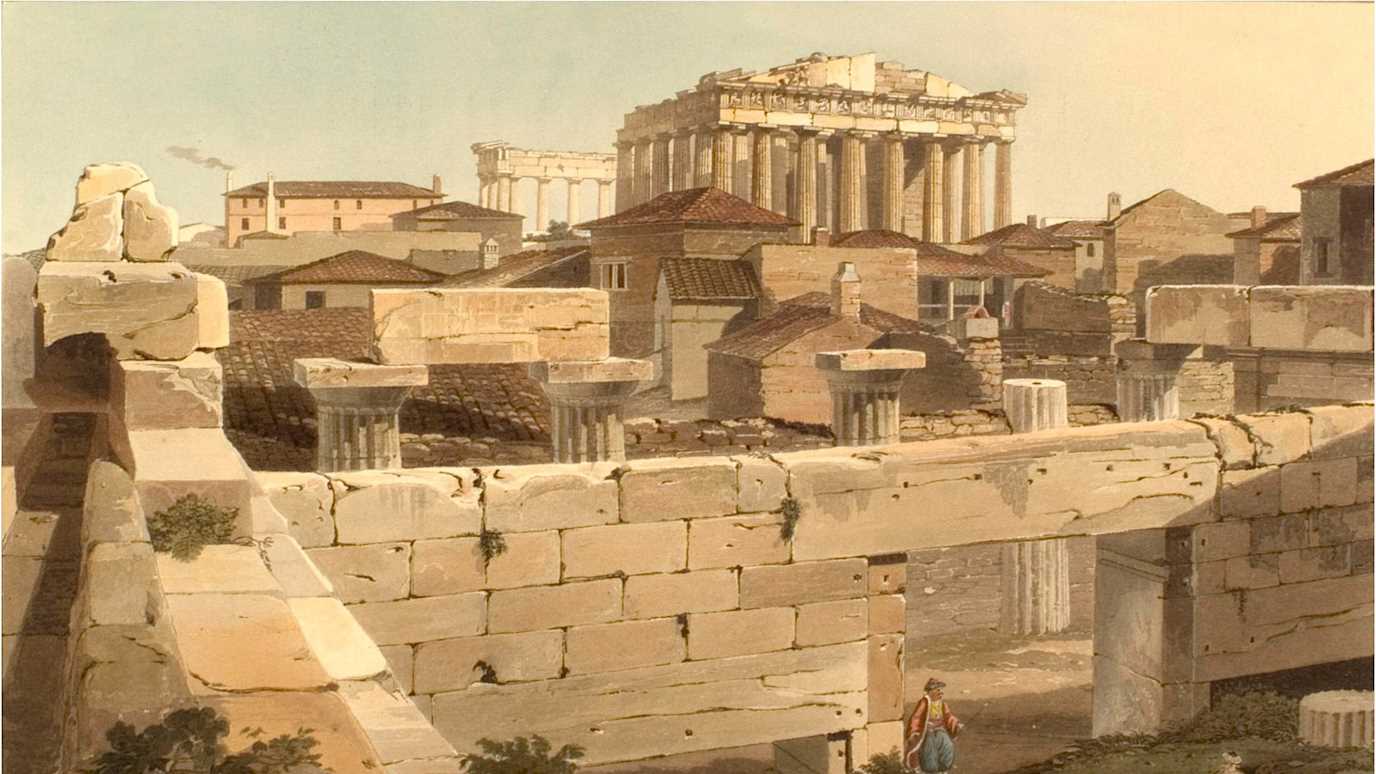

It seems to me that there is only one answer to that: Athens. The reasons are historical, archaeological, and political. Taking the Marbles to London turned them into pure art. We are supposed to admire the workmanship and style. But the Marbles were so much more than pure beauty. They are/were a representation of the Athenian community. The Parthenon was the religious centre of Athens for millennia and the Marbles are part of that heritage. As Elgin transported them to the Piraeus, the inhabitants of Athens protested: part of their culture was being stolen. To understand the Marbles best, we need to see them in their urban, archaeological context and alongside the remains of the community that built and first valued them. In museological terms, they are far better displayed in the bright sun of Athens, in the spectacular Acropolis museum, than in a room in London. Why should an Athenian have to come to London to see the Marbles rather than a Londoner go to Athens?

There are other political reasons to return them: Britain struggles with the legacies of colonialism. It poisons elements of our cultural life and is weaponised by those who want to divide us. But our community was not divided by this debate. A university is a place where we need to discuss important issues, rationally and with passion. It is our function to talk through difficult issues and pose controversial questions.

In the discussion that followed the lecture, our community came to together to talk. We had about 150 people in the hall. Friends, members of the public, academic staff, post-graduate students and our undergraduates had their say. Many representatives of the Greek community came to join us, including staff from the Greek Embassy. One of the most eloquent contributions came from a first-year student, less than six months into their degree, happy to voice her opinion in front of such an audience.

The event was a brilliant example of what we do: we talk about important issues and we do that together and with respect. We value everyone from our first years to our professors. We take our debates into the community: no ivory tower for us.

The past is always with us. We can’t make a better future without it.

With many thanks to Angelos.

For a recording of the event see https://youtu.be/PQpwPaTUU_Q?si=dl1NtgnO2frg_1Gi

For more on Classics and modern issues, see https://www.royalholloway.ac.uk/research-and-teaching/departments-and-schools/classics/news/studying-the-classical-world-classical-views-on-modern-issues-11th-july/