Gallery View, Flora: 150 Years of Environmental Change in Cornwall (John Brett’s Carthillon Cliffs above fireplace). Image credit: Penlee House Gallery and Museum

An artist dedicated to the environment, whose practice explores the complexity, diversity and fragility of the natural world, in Flora Jackson selected a series of 19th century paintings featuring West Cornish flora, plant matter and local habitats as setting, background or subject. These paintings, focused on 12 key locations, became the subject of meticulous research. Jackson undertook site visits, explored where the artists had sat, worked from and observed, read the studies of historic botanists, engaged with contemporary specialists and sought to figure out: how has the natural environment depicted by the 19th-century artists changed in terms of plant distribution, habitat formation and destruction, species loss and (invasive) species gain? Bigger questions came afterwards: why, how and even does it matter?

The research undertaken for the show prompted discussion of issues such as climate change, agricultural modernisation and urbanisation, with the picture presented for most of locations Jackson studied looking quite bleak – they have been subject to a lot of loss. A few experienced substantial gains of species through garden and horticultural escapes, but this still ultimately represents a loss of natural habitat.

Jackson’s own landscape paintings, which feature in the show, help to illustrate this change. They were painted on location in response to the works and locations represented by the 19th-century artists, though Jackson draws a distinction between their more strictly observational practice and his own. He does not simply replicate what he sees, but also enjoys paint for paint’s sake - the marks he makes. He is driven by beauty, but also his knowledge and awareness of the natural world. Environmental concerns were not as immediate in the 19th century. Natural rhythms and ways of rural life still hadn’t been majorly disrupted in most of these locations through big machines and chemical sprays. They were often painted due to their pleasing aesthetic, shapes and colours. Jackson’s concept as a landscape artist is different. It’s a subject he’s chosen to work with because it motivates and concerns him.

Carthillon Cliffs

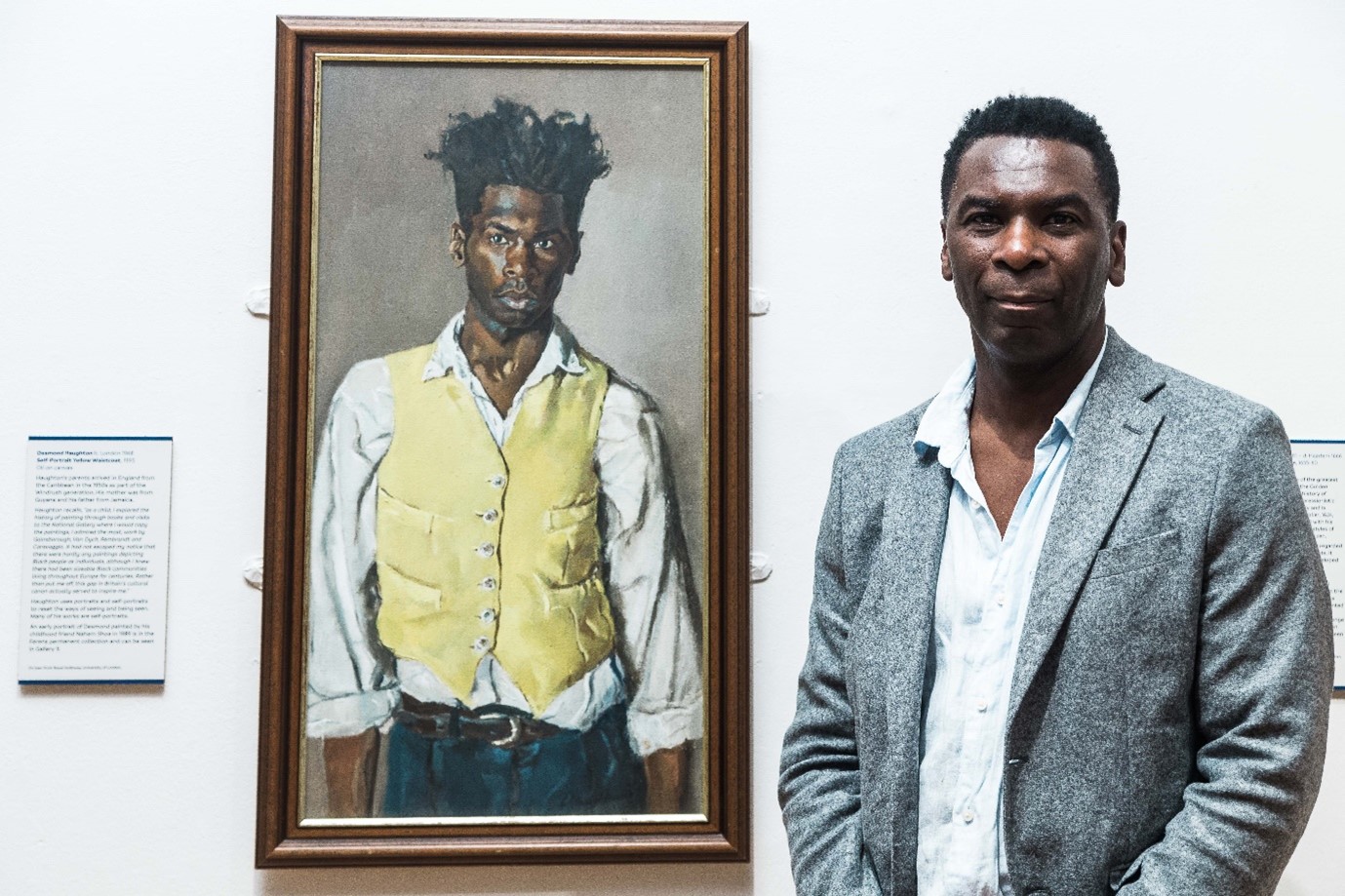

John Brett, Carthillon Cliffs, 1878, oil on canvas, Royal Holloway Art Collection.

Jackson requested to loan Royal Holloway’s Carthillon Cliffs (1878), normally on permanent display in the Picture Gallery, for its beauty. A bright, colourful, attractive painting, which uses oil paint so sparingly it gives feeling of watercolour, Jackson made the painting the focal piece of his show. Caerthillian Valley, near Lizard Town, which the painting depicts, is also an incredibly well-known location in botanical circles. It has been regarded as a hotspot of biodiversity from just before time Brett painted it, and certainly afterwards. It is a coastal Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) with several Red Data rare and endangered plant species.

In the mid-19th century, the botanist Reverend C. A. Johns remarked of diversity in the Caerthillian valley, “A sloping bank on the right hand of Caerthillian valley, about a hundred yards from the sea, produces, I think, more botanical rarities than any other spot of equal dimensions in Great Britain. Here are crowded together in so small a space that I actually covered with my hat growing specimens all together of Lotus hispidus, Trifolium bocconi, T. molinerii, and T. strictuni. The first of these is far from common, the others grow nowhere else in Great Britain.” With 14 species in this single valley, Caerthillian remains the richest spot for clovers in Britain.

Land Quillwort (Isoetes histrix Bory) was first discovered in mainland Britain when it was found at Caerthillian in 1919. A recent re-survey of the Land Quillwort indicates a massive decline (more than 90%) in total population size since 1982 with the loss of several major sub-populations. The factors responsible for this are probably climatic changes, particularly in the pattern of rainfall, and management practices, such as the reduction in grazing.

Remarkably, the painting by Brett shows sheep grazing. Recently, the National Trust and Natural England, who manage this area, have restarted a grazing programme in Caerthillian using ponies and cattle. They had previously been unable to ascertain for certain that this area had historically been grazed, and thanks to conversations with Jackson about Brett’s painting, they had the evidence they needed to make changes to their management of the landscape.

Kurt Jackson, The hot botanical hotspot, thyme, lichen, vetch and wild carrot. Across to Kynance, 2024, mixed media on museum board ©Kurt Jackson

In painting his response to Brett’s piece, The hot botanical hotspot, thyme, lichen, vetch and wild carrot. Across to Kynance (2024), Jackson found that Brett had been creative – both with the title of the painting (which depicts a view just outside Caerthillian) and with the landscape itself (which he somewhat rearranged). For Jackson, who – like Brett – worked en plein air at his easel among the tourists in summer, it was the wild carrots that stole the show. They carpet the foreground of his painting making merry company with the surrounding botanical bounty and demonstrate Jackson’s pure enjoyment of paint.

Written with thanks to Penlee House Museum and Gallery and to Kurt Jackson for his time sharing his reflections on the exhibition and his work.

Brett’s Carthillon Cliffs will be on show at Penlee House Museum and Gallery, Penzance, until 11 January 2025: https://penleehouse.org.uk/exhibition/flora-150-years-of-environmental-change-in-cornwall-curated-by-kurt-jackson/

Gallery View, Flora: 150 Years of Environmental Change in Cornwall. Image credit: Penlee House Gallery and Museum

Gallery View, Flora: 150 Years of Environmental Change in Cornwall. Image credit: Penlee House Gallery and Museum

Gallery View, Flora: 150 Years of Environmental Change in Cornwall. Image credit: Penlee House Gallery and Museum

Gallery View, Flora: 150 Years of Environmental Change in Cornwall. Image credit: Penlee House Gallery and Museum