Posted on 18/05/2019 by Felix Driver

All the talks presented at the Mobile Museum Project Conference, Collections in Circulation, which took place at Kew on 9-10 May 2019, are now freely available via a podcast through the Backdoor Broadcasting Company.

This conference brought together scholars and curators from a wide variety of institutions, disciplines and countries to consider the mobility of collections, past and present. The conference papers addressed diverse themes in the history of the circulation of objects and their re-mobilisation in the context of object exchange, educational projects and community engagement. For a conference of such a scale, with around 100 delegates, discussion was remarkably open, continuous and enriching.

If a conference on the mobility of objects and collections seems very much of the moment, that’s because this event reflected ideas currently reaching across a swathe of academic disciplines and indeed museum practices and politics out there in the world. In much of our work for the Mobile Museum project, as at this conference, we are seeking to explore processes of circulation historically in order to re-examine, inform and perhaps unsettle our knowledge about the way collections have evolved over time and over space. The first fruits of our research on the mobility of Kew’s Economic Botany Collection are beginning to appear, for example in the Journal for the History of Collections.

Many of the conference speakers considered the ‘re-mobilisation’ of collections to serve new purposes in the present, as for example in papers by Luciana Martins on the re-use of biocultural collections (notably those of Richard Spruce at Kew) in Amazonia, Paul Basu on contemporary re-engagement with colonial anthropological collections (including anthropological texts, photographs, objects and film) in West Africa, Alice Stevenson (using the example of Egypt’s dispersed archaeological heritage), Claudia Augustat (in the case of Amazonian collections in European museums) and Karen Jacobs and Steven Hooper (on the regeneration of aspects of Fijian material culture). All these papers examined - sometimes critically, sometimes hopefully, always with sensitivity to Indigenous ways of knowing - current attempts to reactivate ethnographic and botanical collections through their mobilisation, and what this might mean for education, heritage and livelihoods in their source regions today.

This meeting took within the walls of a scientific institution once deeply embedded in the structures of empire. The history of empire and the imperatives of decolonial challenges to its structures, including those of the museum, loomed large in papers by Caroline Cornish, Felix Driver and Mark Nesbitt on Kew’s Economic Botany collection and by Daniel Simpson on British naval collecting and attempts to preserve the integrity of specimens in circulation. The various kinds of economic, scientific and biophysical mobility reflected in the history of natural history collections were examined by Joshua Bell in a compelling keynote address on the 1928 U.S. Sugar Cane Expedition to New Guinea. Evoking recent work on Indigenous intermediaries, Bell showed us something of the hidden histories of Indigenous agency collections latent within even the most unpromising of colonial narratives.

Histories of object-based learning and exchange across the spaces of the museum, the botanic garden and the school were addressed in a number of contexts. Catherine Nichols, building on her impressive studies of artefact exchange in museum anthropology, raised wider issues about the capacity of texts, drawings, casts and duplicates to serve as proxies for type specimens, as illustrated in the archives of the Smithsonian and the Pitt Rivers Museum. Sally Gregory Kohlstedt moved the focus towards the botanic garden, using case studies of gardens in New York and Brooklyn to situate the role of plants and plant-derived objects in education and training during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The pairing of her paper with Laura Newman’s account of the mobilisation of plant specimens for use in London classrooms during the same period provided an opportunity for reflection on the possibility of a comparative and indeed global history of object-based learning in nature study.

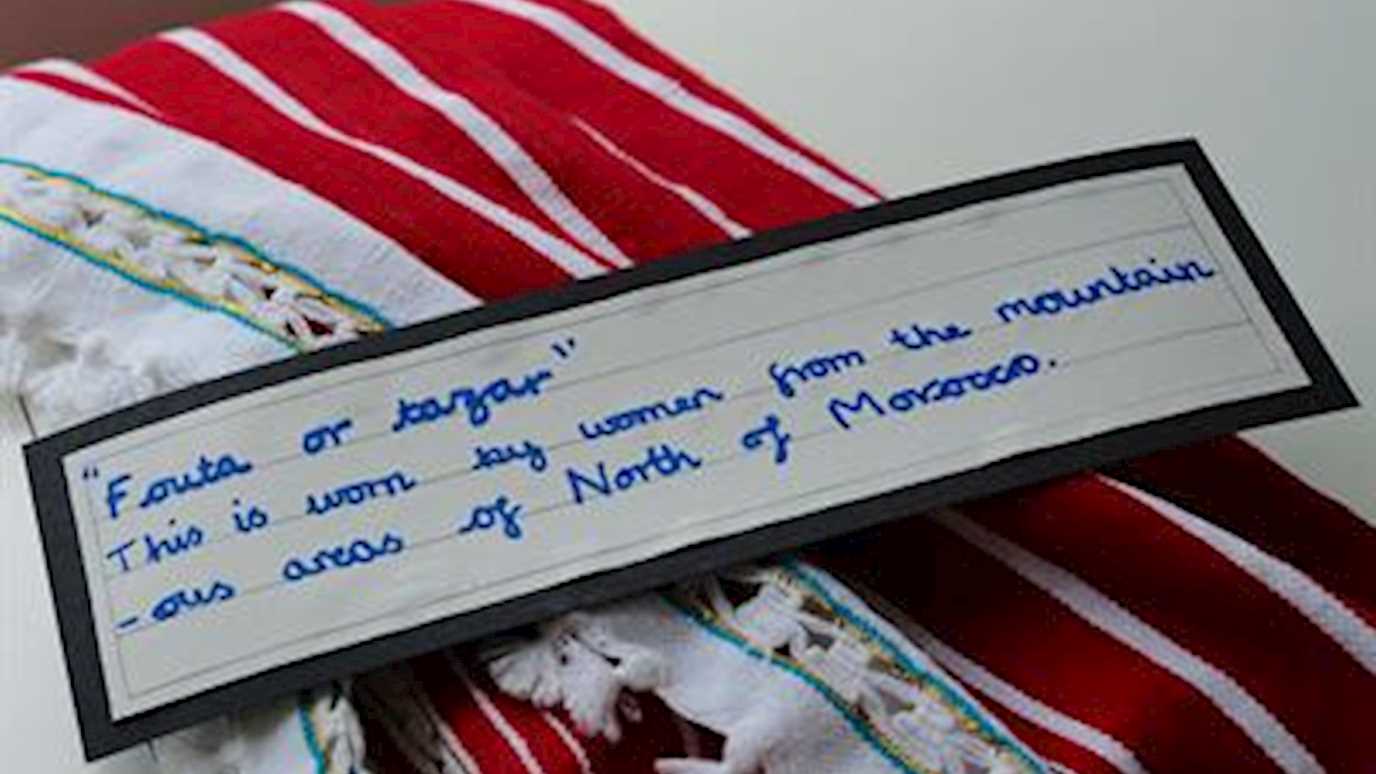

Given our location at Kew, an agglomeration of remarkable botanical collections (including not just the gardens, but also dried plants, seeds, artefacts, archives, books and artworks), it was fitting that delegates were given a glimpse of these materials during the conference. Thanks to the work of staff in Library, Art and Archives, we were shown a superb display of relevant archive material, while Mark Nesbitt and Caroline Cornish gave tours of the Economic Botany Collection itself. Tony Kanellos, meanwhile, did an impressive job in highlighting the transformation of Adelaide’s Museum of Economic Botany into a multifunctional space for the engagement of a variety of publics. The capacity of such sites, not just to gather materials and expertise from across the globe, but to present them in ways which address contemporary issues in inspiring ways, makes them truly fascinating from the perspective of non-botanists and botanists alike. This links to a wider theme running through the conference, namely the actual and potential contribution of arts and humanities researchers to enhancing the understanding of scientific collections. The great power of places like Kew lies in their collections, in all their forms: and unlocking that power, making it more available, is a task which surely requires the kinds of historical, interpretative and communicative skills associated with the arts and humanities.

During this conference - in its interstices at tea breaks, reception and tours as much as within the formal sessions - there was evidently much ruminating, some mobilising and above all lots of circulation. Martha Fleming’s concluding plenary talk (‘What goes round, comes round: mobility’s modernity’) reminded us of the importance of not dwelling too much in the nineteenth century, of asking big questions of big data and of a healthy scepticism towards the promise of digital media. This skilfully nuanced appeal for broader and more diverse approaches to the history of modernity, and for a greater appreciation of the power of collections in engaging with contemporary environmental crises, provided a fitting end to the conference, though not of course to the circulation of its key ideas. Thanks to the Backdoor Broadcasting podcast, those not able to attend the event can hear all the talks, and glean some of the discussion around them that continues to resonate.