Posted on 03/05/2018 by Caroline Cornish

Having just returned from a 3 week field trip in the USA I’ve been thinking about the ‘special relationship’ claimed by many to characterise US-UK interactions both past and present. This relationship, I have learnt from my work on the Mobile Museum project, considerably pre-dates Winston Churchill’s first use of the term in 1946. In the late 19th century, museums on both sides of the Atlantic were engaged in networks of knowledge exchange facilitated by the flow of people and objects travelling in both directions. Kew, whilst considered first and foremost an apparatus of the British Empire, had a far greater number of transactions with institutions of science in the USA during this time than it did with the British dominion of Canada. And the Kew Museum of Economic Botany was no exception with quite literally hundreds of specimens, artefacts, images, letters and publications exchanging hands with museums at Harvard, Philadelphia, and Washington in particular.

Then and now: Polynesian exhibit, Philadelphia Commercial Museum early C20 [left] and Harvard Economic Botany Collection. Image courtesy of Independence Seaport Museum

I began my journey at Harvard where Asa Gray, one of William Hooker’s long-standing correspondents, was appointed Professor of Botany in 1842. In 1858 Gray wrote to his Kew mentor, announcing that, ‘in humble imitation of Kew, I am going to establish a Museum of Vegetable Products in our University.’ Thus began a long period of object exchanges between the two parties. As at Kew, the Harvard museum no longer exists, but the collection is available to researchers and is stored in the atmospheric attic of the Harvard Museum of Natural History. I spent a week there tracking down objects sent by Kew between 1880 and 1906. The accession registers have long since disappeared so I was largely reliant on word-matching Harvard databased objects to a list of distributed specimens taken from the Kew Museum exit books. But I was also able to spot ‘Kew’ objects by their distinctive labelling, once produced on Kew’s own letterpress.

After a week I travelled south to Philadelphia, dubbed the ‘Athens of America’ in the 18th century and broadly recognised as the cradle of North American museums of science. My interest here lay in recovering objects sent by Kew to the Philadelphia Commercial Museum [PCM] during the belle époque. The museum’s collections were dispersed in 2001 amongst a range of city institutions, two of which, the Penn Museum and the Independence Seaport Museum, I visited. The task here was complicated by the fact that the PCM repackaged and relabelled all its acquisitions into a standard format, thereby removing all traces of previous ownership. Nevertheless, I was able to identify a number of objects sent from the Museum of Economic Botany―plant derivatives as well as made objects―and learn more about the phenomenal Commercial Museum in Philly’s many libraries and archives.

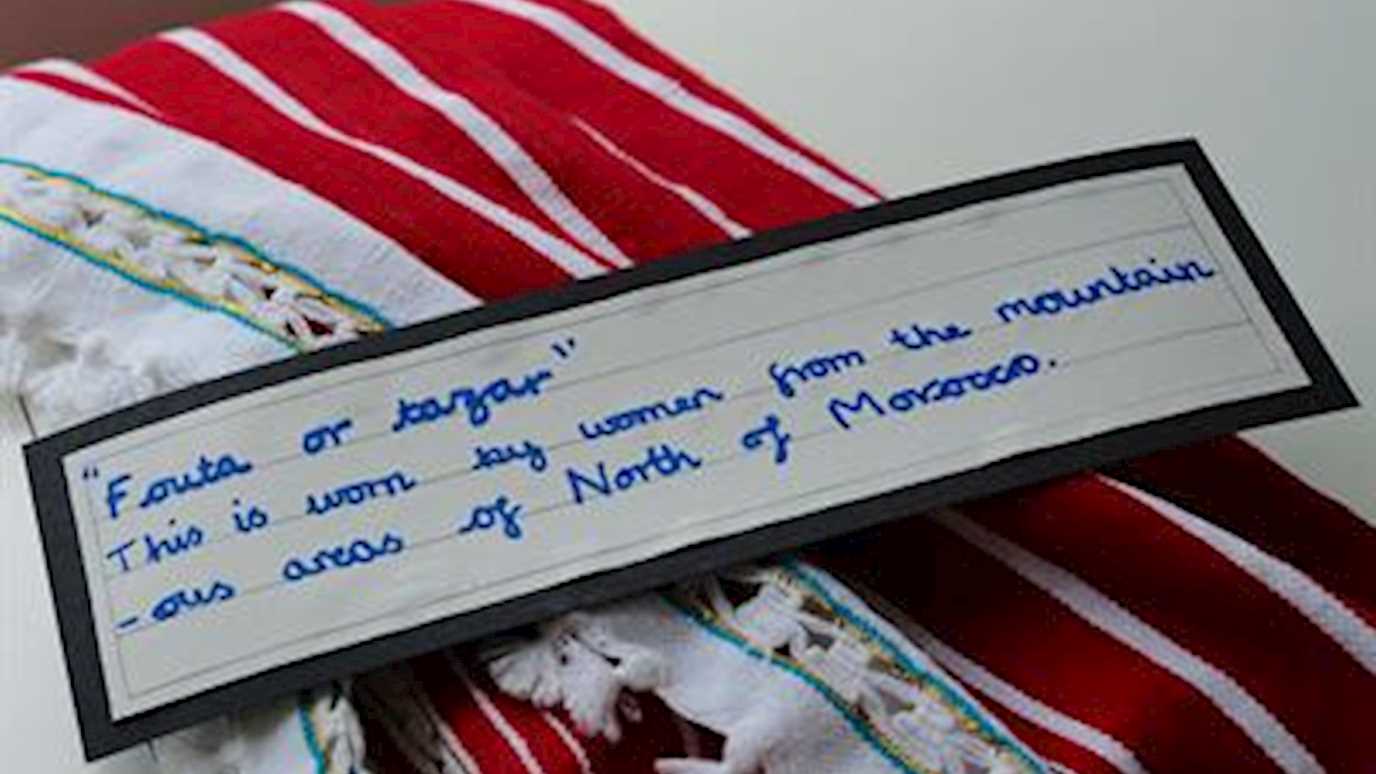

Finally to Washington DC and the Smithsonian Institution [SI]. Previously, in 2016, I had discovered materia medica, woods and ethnographic items sent by Kew in the past; this time I focussed on textiles which curator Madelyn Shaw had located prior to my visit in the vast out-of-town SI stores in Maryland.

The data gathered will be entered into an online database, thus enabling curators with Kew holdings to learn more about the objects in their collections. This in turn will create new users of these collections. But data aside, the trip enabled the formation of new networks and the refreshment of existing ones; personal visits engender good will and engagement in a way that emails and video calls cannot. I’d like to think that this trip made its own small contribution to the special relationship!