Read My Lips, the current exhibition at East London gallery Auto Italia, presents a selection of work from North American activist-artist collective Gran Fury (1988- 1995).

In the face of indifference and inaction on the part of the American government Gran Fury, in collaboration with ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) produced a public information campaign cum artists’ intervention designed to inform and educate about HIV/AIDS and to destigmatise its sufferers. In addition they organised practical initiatives such as needle-exchange programs for injecting drug-users – something frequently not provided by civil authorities in the United States.

The work on display at Auto Italia dates from 1987 – shortly before the founding of Gran Fury – to 1995 when the collective disbanded. It ranges from relatively conventional public information posters to bold and confrontational pieces featuring explicit sexual imagery and iconoclastic statements attacking political and religious figureheads – Ronald Reagan and Pope John Paul II amongst them. The collective employed a variety of strategies derived from site-specific art, post-modern appropriation and detournement, and queer activist movements. In order to achieve their stated aim of ‘exploiting the power of art to end the AIDS crisis’ the work had to be striking, direct and ideally unforgettable.

The Gran Fury campaign also demonstrates how the void left by the governing authorities had to be filled by voluntary organisations. It was clear that the response of the Reagan administration, under some pressure from religious and right-wing conservative groups passed moral judgment on those infected with HIV and dying of AIDS. (Texts from the period such as Tony Kushner’s Angels in America and David Wojnarowicz’s Close to the Knives (both 1991) attest to the extent to which the Federal Government of the USA was unwilling to address HIV/AIDS.)

By stark contrast in 1987, the year before the founding of Gran Fury, the UK Government – Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Government - took direct action. Spurred by his experience visiting an AIDS ward in San Francisco in 1986 [?] Health Secretary Norman Fowler decided that it was necessary to launch a public information campaign to warn people of the dangers of HIV infection based upon the best scientific evidence available. This evidence-based approach to public health (and one which, above all, adheres to the principle that avoidable deaths should be prevented where possible) was in clear opposition to the attitude of the United States’ Government. This may say something not only about Fowler personally, but about the British attitude to healthcare in general – that it is considered to be a societal, not individual responsibility.

However, Fowler faced objections - from within the Cabinet and beyond – of the ilk that were influencing US decision-making. Here figure-heads of authority (Thatcher, the Chief Rabbi) were not to be attacked, but tactfully persuaded or evaded. In spite of this opposition, the nation-wide Don’t Die of Ignorance campaign was launched: an information leaflet was distributed to every household explaining that the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) caused AIDS and how best to avoid HIV infection. These leaflets were accompanied by a – now infamous – advertising campaign (with TV adverts directed by Nicolas Roeg and featuring music by Brian Eno) which stressed that the risk of infection was universal, not limited to certain groups in society. This campaign was in part the result of focussed and persistent lobbying on the part of civil society organisation and charities such as the Terence Higgins Trust (THT). It was hailed as a success and imitated by governments in France, Spain and Italy – but not the USA.

Read My Lips illustrates how art and activism filled what has subsequently been exposed as a policy vacuum in American governance. Hindsight has shown that the high-moralising of certain groups and individuals in the USA lead to the unjust and unequal provision of healthcare. The exhibition also demonstrates differing trans-Atlantic attitudes to the role of Government and the possibilities offered by a nationalised health service. Without the added complication of health insurance, the British response could be conducted universally and on all fronts. No-one could be refused treatment and this in turn – when dealing with a virus such as HIV – leads to society-wide benefits. As policy today shows, the most effective way to combat the spread of the virus is through access to testing and effective treatment regimes. To this day one of the major cultural barriers to coming forward for testing and treatment is stigma and it was this that the Gran Fury campaign addressed directly and which the Don’t Die of Ignorance attempted to avoid by addressing as broad a constituency as possible.

By 1994 roughly 244,003 people had died of AIDS in the USA - compared to 8,901 in the UK – and AIDS accounted for 2% of all deaths and was the leading cause of death amongst people aged 25-44. Today cumulative mortality figures are 658,507 (USA) and around 23,828 (UK) [Public Health England]. The current situation in the USA, despite major efforts, is still much worse than other developed nations. The USA currently has an HIV incidence of 0.3% compared to 0.16% in the UK. This equates to around 1.1 million people in the USA and 100,000 in the UK. Taking into account relative population size the USA’s HIV/AIDS epidemic is – quantitatively – twice as bad as the UK; 100% worse, to use alternative language. For example, around five times as many cases of HIV result from the sharing of needles (2% vs 10%). Minority groups, the marginalised, disenfranchised and the poor are still the worse affected: incidence in the African American community is 1.27% - four times the rate for the population as a whole. Whilst African Americans make up only 12.6% of the population of the USA, they account for 43% (471,500) of those living with HIV and 44% of new diagnoses. In the UK, whilst the picture is better overall, the vast majority of new HIV diagnoses are in gay and bisexual men and the heterosexual black African community.

Read My Lips gives an account of art taking action where public policy – and politics more broadly - fail. Gran Fury’s declaration to exploit the power of art to end the AIDS crisis shows us that HIV/AIDS is not simply a medical issue, but a cultural, societal one. The victims of AIDS are frequently those farthest from power, those who do not or cannot participate in mainstream politics. In addition to this, Gran Fury’s work demonstrates where the politics of identity extend beyond the question of political representation and become a matter of life and death.

Read My Lips is at Auto Italia until 16th December 2018.

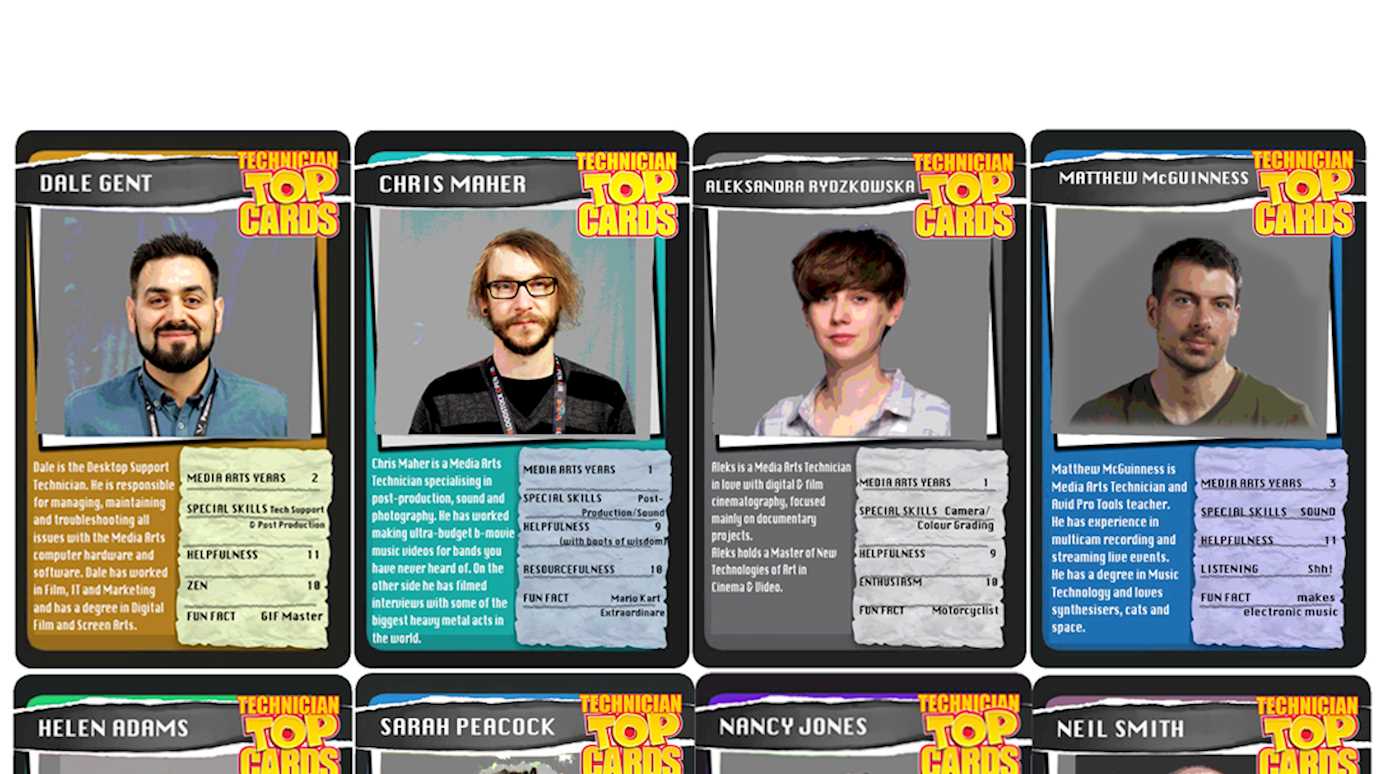

Find out more about studying in the Department of Media Arts at Royal Holloway.

Dr Nick Lee is Teaching Fellow Film & Television Studies in the Department of Media Arts